Sci-Fi Has Always Been Political

There’s a curious case of revisionism surrounding the history of the future making the rounds in fandom. Certain groups, most notably of the depressed juvenile canine persuasion, but hardly limited to them, are making waves about what they claim is a recent phenomenon among the ranks of science fiction authors, their editors, and their publishers to inject distracting, even oppressive amounts of social and political commentary into the novels and short stories they choose to produce.

These earnestly concerned aficionados of the genre pine for the Golden Age when science fiction was awash in rayguns and replicants, alien ass-kicking, monoliths and megastructures, before this new wave of social justice bards inserted themselves into the conversation and ruined their good fun.

There’s just one small, niggling problem with this assessment; Sci-fi has always, even primarily, been political. It was just never questioning their politics before. It was never challenging their preconceptions, or calling out their cultural biases. As they say, you never forget your first time.

Instead of embracing the call to turn their attentions inward for a little self-reflection, many among the community of sci-fi fandom instead looked backwards to an age when all the voices sounded suspiciously like their own. But in the process, they’ve conveniently forgotten the point of the seminal work of some of the genre’s most influential authors.

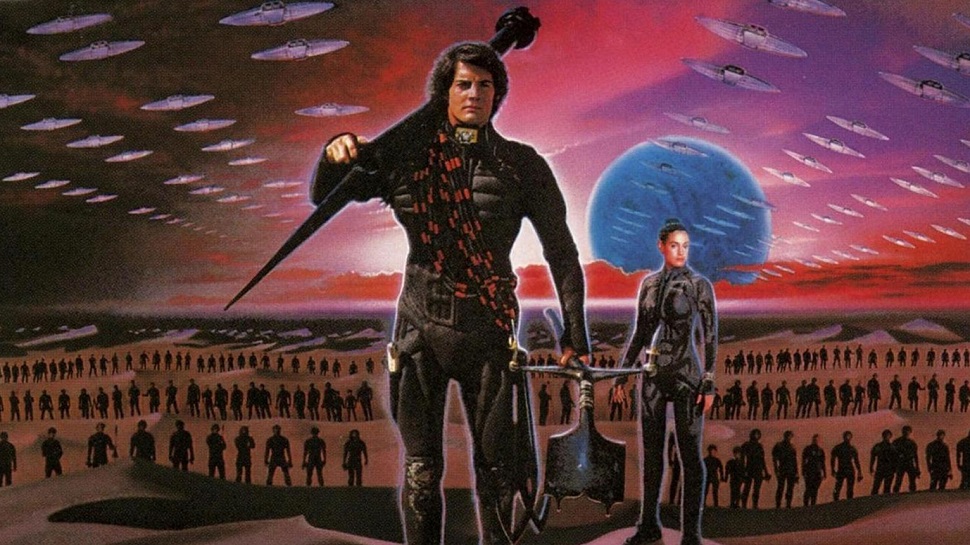

Frank Herbert’s masterpiece Dune, as an opening example, dives deep into questions of colonialism, treatment of indigenous people, the roles and relationship between religion and government, all wrapped within a powerful allegory for the rising power of the Islamic petrostates in the middle east and the clash of cultures over scarce resources. To say that Dune wasn’t political is simply absurd.

Between 1984 and Animal Farm, George Orwell wrote two of the most memorable novels lampooning government control and overreach from both sides of the political spectrum. Philip K. Dick dealt with fascism and slavery in The Man in the High Castle, as did Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Orson Scott Card wrote one of the most persuasive and beautiful arguments found in literature in favor of religious tolerance, diversity, inclusiveness, and against heteronormativity in his celebrated Speaker for the Dead, not that he meant to, it just sort of happened. Robert Heinlein spent an entire career writing political allegories about war, government, and what it means to be a citizen, evolving from one end of the political spectrum to the other and back again in a decades-long conversation with himself.

Jumping media, there are no end of examples of beloved sci-fi movies and television tackling themes of racism, sexism, and unequal treatment of ‘the other,’ Star Trek and Dr. Who chief among them in all their various incarnations.

The only critical difference is today, the people telling these stories aren’t imagining them. They’re writing from their own lived experiences of inequality and discrimination, persecution and violence. As a result, their stories bring the kind of raw-nerve sharpness that comes with authenticity. New wave authors like Ann Leckie, Charlie Jane Anders, and Liu Cixin make a certain type of reader uncomfortable, because the underlying truth of what they’re writing is so much closer to the surface on an emotional level, and therefore harder to ignore.

Sci-Fi is currently bookended by two remarkable women. From its very first work in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus, straight through to last year’s Hugo winner, N.K. Jemisin’s Obelisk Gate, Sci-Fi has returned to one question more often than any other; “What makes us human?” Shelley asked who qualifies. Almost two-hundred years later, Jemisin argues no one is qualified to answer. The conversation will continue for centuries more, and new voices will be invited to join, from ever more diverse backgrounds, adding their own color and patterns to the tapestry generations of storytellers have woven.

Eventually, even authors of Artificial Intelligence, the ultimate children of sci-fi, may have to fight for a seat at the table to tell their stories. I’d like to think that, if I’m still breathing, I won’t have grown so ossified that I’m shaking an auto-walker in their direction, complaining about how they’re ruining sci-fi for ‘organic’ humans.

Jason Chiles - 01/08/2018 - 3:58 am #

You’ve just gained a new fan to follow you…now can you pass me a towel so I can clean up all the Coke I just spurted out at the line:

“Orson Scott Card wrote one of the most persuasive and beautiful arguments found in literature in favor of religious tolerance, diversity, inclusiveness, and against heteronormativity in his celebrated Speaker for the Dead, not that he meant to, it just sort of happened. ”

Best summation of just about anything Card has tried to do…now I need a new keyboard.

OneZero - 01/08/2018 - 7:47 am #

Hmph. Maybe OSC meant to write it just like it turned out, just like all his other works turned out. Maybe he’s more than the caricature Mormon extremist he’s been painted as.

Similarly, I have seen Mr. Tomlinson evolve over … what? 15 years? … from “bjinthebathroom” to a person whose opinion I respect, even when I do not agree.

OSC’s book on characters should be required reading for not only authors, but anyone who wants to understand real people and why they do what they do.

Is Pat the guy who brings a well-done figure of a transgender woman with a hard-on to Wonderfest just to push boundaries? Yep. Is he also a thoughtful commentator on current events? Yeah, that too.

People are a mess – whether OSC, Pat or me. maybe it would be best if we all gave each other the benefit of the doubt, passed the spliff and cracked open a can for each other, instead of judging and hating.

Patrick S. Tomlinson - 01/09/2018 - 4:00 am #

What I meant, and what I think Jason was identifying with, is how OSC failed, or chose not to, apply the same highly persuasive arguments he made for inclusiveness in SftD to his own social and political advocacy, especially in regards to equal rights for the LGBTQ community.

He seems to have quieted on those issues in more recent years, although if that’s due to a change of heart, or simply a surrender to the new reality of same sex marriage, I couldn’t say.

Patrick S. Tomlinson - 01/09/2018 - 6:31 am #

But yeah, I totally brought that figure.